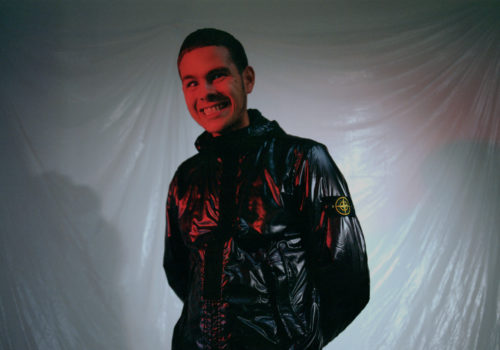

JPEGMAFIA is at the mercy of the music industry

Video by Bobby Zithelo

Words: Dylan Murphy

Photography: George Voronov

Styling: Michael O’Connor

Video: Bobby Zithelo

Right before COVID-19 halted concerts across the globe, Baltimore’s adopted son, JPEGMAFIA made his penultimate live appearance in Dublin. Prior to hitting the stage, Peggy stopped by District’s office to speak to Dylan Murphy about clinging to music in its purest form and the relentless nature of the industry.

In the lead up to my chat with JPEGMAFIA I prepared as much as possible. I watched every video interview I could find, downloaded deep cuts from the early 2010s and even found his old youtube channel where he posted all his early beats. I framed my questions meticulously, perpetually worried about finding myself on the receiving end of the sharp one-liners laced throughout his music and often deployed against “fake woke” posers and the alt-right. For those unacquainted with the New York-born spitter, you should know that he has spent his entire career challenging the established order.

In retrospect, I really should have guessed that no matter how much I prepared, our encounter would not pan out as expected. Having just finished the photoshoot in the District office, JPEGMAFIA realises that he needs to buy new shoes ahead of his show in Dublin’s Academy that night. Suddenly, he adjusts his plans. “We can just do the interview as we walk” he announces standing beside his tour manager at the top of our stairs. With those words my plan of a sit-down chat with the rapper went out the window.

Having moved between different states and various cities growing up, Barrington DeVaughan Hendricks or ‘Peggy’ as he is now known to his cult fanbase has led a largely nomadic lifestyle. When he was a teen in Louisiana he was recruited for the US Airforce and was stationed in numerous places across the globe including Japan and Kuwait. It was in his quarters as a young recruit that he would hide away with a laptop in his free time making beats before he was honourably discharged and moved to Baltimore. The East coast city would become his de facto hometown where he would go on to create his breakout record ‘Veteran’.

Chatting about that very record, we leave the building and are hit by Dublin’s cool March air. He toured the album with experimental hip hop outfit Injury Reserve and in the process became close friends with all three members. It was here he cemented his reputation as a confrontational, post-internet artist putting posers to the sword and challenging the alt-right through songs like ‘I Cannot Fucking Wait Til Morrissey Dies’, ‘Libtard Anthem’, and devastating lines such as ‘AR built like Lena Dunham’. I was lucky enough to see the two acts perform in Colorado on that very tour and so it was an easy ice-breaker.

“I really appreciate them for giving me that slot”, he tells me as we recklessly tried to dodge cars whilst crossing the capital’s busy streets before narrowly swerving another that loudly blared its horn.

“Damn bro! I reacted super late as shit, let’s get the fuck outta here” he says as we march towards Grafton Street.

[Editor’s Note: Injury Reserve, the group on the receiving end of Peggy’s praise in the previous passage would go on to suffer a devastating loss in the next few months. Groggs, one of the group’s rappers and a close friend of Peggy’s tragically passed on July 1 of this year, not long after this interview.]

The other thing that struck me about that show in a dingy basement was that JPEGMAFIA didn’t use a DJ, he simply brought his laptop and hit the play button as if it was an on/off switch for a mosh pit.

Clearing his throat before talking he tells me, “The original intention was I couldn’t afford a DJ and then it kind of morphed into what it is now. It’s a symbol.”

“No matter what I’m doing, No matter how much I advance or how big I get when I go up there, I just have my laptop and me. I might get more laptops or it might get more complicated but the core of it is beats and rhymes, that’s it” he says.

With one eye on a Footlocker that he can grab some new shoes from, he interrupts himself with a disclaimer, ”It sounds real corny, but that’s what the core of hip hop is – beats and rhymes. That’s what Dougie Fresh and them was going up on stage with so I’m doing the same fucking thing. It’s just 2020 and I’m showing them it still works.”

While his own sound is an almost wholly unique style that meanders between the screams of punk and hardcore and even the auto-tuned croons of 2000s RnB, it’s true that in the live setting his art is grounded in the foundational principles of hip hop. However, there’s a type of emotion embedded in his music and his live shows that doesn’t subscribe to the largely misogynistic and unsympathetic genre he operates in. JPEGMAFIA is a walking contradiction and it is essential to his artistry to fiercely uphold these opposing ideals.

“People pay money to come see me. I want them to touch me and I wanna go in there with them and for them to see me dying up there. He continues, “because if that’s not what they are getting then what is the point?”

“If you are getting a real calm version of me or something like that you can just listen to me at the crib. When you are coming to me I want you to get the full me.”

This unapologetic approach hasn’t been easy to maintain but JPEGMAFIA has found solace in the online community he has created with his fans. It is a digital realm defined by its fiercely nonconformist attitude as well as its surprisingly empathetic familial spirit. The relationship between fans and Peggy feels like a therapy session-meets-exclusive club. It’s a community of outcasts and oddballs seeking a safe space to express their innermost woes as well as profess their admiration for Peggy. JPEGMAFIA acts as chair for these meetings whilst actively listening to his fan’s struggles. This reciprocal relationship is made manifest in Peggy’s chaotic live shows. Standing in the crowd, it is instantly clear that performer and audience already share an intimate connection.

However, while he can rely on his supporters to hold him down, the same cannot be said for the industry as a whole. Time and time again he has lamented the flagrant profiteering of musicians’ records by the gate-keepers of the industry. A frequent point of frustration is the lack of respect for the art of it all, as good music is repeatedly held to ransom by the red tape that litters an emotionless business. Pausing on the footpath near the Spire, I ask if at times he felt at the mercy of the music industry. Taking a beat, he nods, “I’ve never had anyone ask me a question like that man… that’s absolutely true.”

“Yeah, I feel like sometimes my fans understand me more than my fucking management,” he says laughing as he looks at his tour manager who chuckles in agreement.

“You feel me? Nah real shit like, they REALLY get it. I’ll put something in my songs and my fans will detect it, pick it apart, look at the meaning. Even if it is wrong, the effort and the care they put into it is because they realise the care I put into it. The industry does not give a fuck bro. It’s all just a product to them.”

Chirping in, his tour manager says exaggeratedly “It’s all just retail” as if it’s a running inside joke within Peggy’s exclusive club.

“It’s just retail man”, Peggy reaffirms in agreement.

What is even more impressive given the current climate is that Peggy broke through in his late twenties. These days, Tik Tok gives swathes of teens access to their 15 minutes of fame in an instant. Thanks to an unpredictable algorithm these largely inexperienced artists are exposed to thousands of viewers without needing to cut their teeth in the traditional battlegrounds of the music industry. Meanwhile, at the age of 30, Peggy confesses that he is still struggling. After years of trying, he worries that simply being himself may never be enough. Asking if constant queries about his character, motivations and artistry have taken a toll on him he answers with no hesitation, “That’s my entire life, being uncomfortable.”

“This is a real woe is me type thing, but all my life, I’ve always had to adjust who I am for other people and dumb myself down. It’s just the strangest shit and now… In the industry, I find myself in the same situation with my music.”

“Everything I do someone has a problem with. The other day I put up ‘BALD!’ and it got flagged on youtube because it had a blunt at the beginning of the video.”

Continuing with a dry sense of sarcasm he says, “ Imagine. A blunt. In a rap video.”

“The AUDACITY.”

“But I find myself in these positions and there’s never any answers. I’m just saying, when you aren’t that big, people just don’t fucking care. You really have to fight for your spot.

I am at the complete mercy of the industry and that sucks ass. I see so much shit wrong with it and I feel like I know I am not the first person to feel like this, but sometimes I feel like I’m saying something that no one else cares about.

Maybe fifty years from now people will, but it’s gonna be too late by then.”

“But yeah to answer your question I feel completely at the mercy of the industry, it’s really sad. For someone like me to exist and even get to this point is literally a miracle, I had to fight and scrape.”

“Literally, that’s my entire life, just being in situations where people are like ‘you can’t be you’, and I have to work around it. Yeah bro, I don’t really say that kind of stuff because I don’t like to be like ‘oh my god, woe is me’ or whatever, but that’s really what it is.”

“I feel completely at the mercy of the industry, it’s really sad. For someone like me to exist and even get to this point is literally a miracle, I had to fight and scrape.”

– JPEGMAFIA

Peggy’s vicious independence is admirable, but it is becoming increasingly apparent that it’s out of necessity. It’s a survival instinct, even after his success he can still only rely on himself.

The DIY and punk ethos that informs his journey is often met with suspicion from the industry as he elaborates. “I am just completely naturally an anti-establishment kind of person. So much so that the establishment detects it in me or something…”

As noisy seagulls squawk above us and their shadows dance around our feet he explains where his risk-taking approach comes from.

“It’s out of necessity man. It’s like, I’m so close to the art and I care so much for it, that I will sit and fight and find ways to make it exist in its purest form. If I’m not here, making sure everything is right, making the crucial decisions and the crucial mistakes that shit will sound completely different. It’s out of complete necessity. I have to because if not the art will come out in some corny, watered-down version that no one will care about.”

We take the natural pause in the conversation as an opportunity to cross the road to the doorway of the Footlocker he’s been eyeing up. Visibly irritated by the muffled pop music playing in the store we step out as he consults his tour manager about where to head for food before the show. After settling on Burger King I circle back to the question of authenticity in the industry. It feels as though for a long time hip hop had a discriminatory approach to praising and endorsing authenticity and I ask if he agrees.

“Yeah that authenticity thing is selective as hell, but no one says that, but it is extremely selective… like authenticity matters on certain rappers and other rappers it doesn’t at all. I don’t know where that line is, it is kinda blurred, and it is the truth. For some people, it can work against them and for other people it can work for them.”

While authenticity is something that either comes naturally or it doesn’t, the motivation behind making music for artists is usually explicit and considered. Kanye West, for example, wanted to change the course of music history and push the boundaries of sound while Kid Cudi wanted to comfort kids going through hard times. Though both of these are also important themes in Peggy’s music, working out what drives him on a day-to-day level is less clear.

“It’s something I’ve really been trying to dwell on because I’ve always just made music and it is the only thing I like to do, you know? It was only until other people started analyzing it ’til I was like ‘what am I doing? What is my purpose with all this?’, and you know what bro… I think I’ve just had such a traumatic, empty life that I’ve dumped myself into the music and I don’t know how to exist in any other way. If I didn’t have the music bro I’d be working in McDonald’s or some shit. I’d be dead or something. I have no purpose outside of that and that is self-imposed, but it is a reaction to people not getting me in any other medium.”

“Music is the medium I’ve loved the most and the only one that’s ever reciprocated it back to me. I can’t lose that shit, it’s a desperation to me so I don’t even know if I have a purpose bro. I think I would just do this if I was making money or not to be honest. If I was on the street, I’d find a laptop somehow and be making beats, it wouldn’t matter to me. I’m just glad I can make money from it because a lot of people don’t and they have the same mindset.”

Pausing reflectively, Peggy puts forward that maybe he doesn’t have a purpose, at least not one that he can put his finger on. “I just make music out of desperation.”

“I think I’ve just had such a traumatic, empty life that I’ve dumped myself into the music and I don’t know how to exist in any other way”.

– JPEGMAFIA

These sentiments live in his music too, with Peggy describing the song ‘Jesus Forgive Me, I Am A Thot’ as “basically a prayer”. There are notable parallels between the prayers of Peggy’s music and the twisted pleas for help in Danny Brown’s ‘Atrocity Exhibition’. I ask how important it was to have someone like Danny Brown thrive as his undiluted self, even in the face of raised eyebrows from his contemporaries.

“Yeah, Danny Brown is one of my biggest influences and after meeting him–– and I listened to this man for ten years––, I feel like I have a duty personally to continue what he did. I’m not saying he stopped doing what he did but I want to continue that legacy because he has opened that door in so many ways and I want to do the same thing for somebody else.”

The same appreciation given to Danny Brown is afforded to fellow Brooklyn natives Flatbush Zombies, who we agree are under-appreciated, but have built an important legacy already.

“It’s like they sacrificed. They were the first through the door and they had to take the hit for it. I realise now that I listen to so much music… that a lot of my favourite artists don’t get appreciated in their time. I’m glad Flatbush Zombies can get appreciated in some way even if it isn’t as much as people want them to” he says proudly over the noise of the passing cars.

“There are artists like Nick Drake who died thinking they were nothing bro and twenty years later this man has people sounding just like him, but he went to the grave a nobody bro. That’s how he left, that’s it. When he died that was what he thought, at his last show two people turned up”

It’s clear that this devotion to going against the grain really ignites a fire in Peggy’s soul, bringing clarity to where his purpose lies going forward. “My legacy matters now because I have made it to a point where I have those kind of fans”, he tells me.

“So it matters a lot to me now – I want people to look back and be proud of what I did when I was here. Whereas before it wasn’t about a legacy it was about desperation. It was just ‘I’m going to be doing this’ and since nobody cared I was just like ‘Good. Keep not caring. I’m going to keep doing this shit because one day hopefully somebody sees it and one N**** fucks with it. That’s all I need because I know I fuck with Nick Drake. I don’t know who else fucks with that N**** but I respect that motherfucker and I’ll say his name in an interview or Robert Johnson or all these people that people don’t remember.”

Continuing defiantly he exclaims, “But I remember them, yo, these dudes that died on 360 deals, dying, rotting, depressed. They are kings though. They are magicians to me, but people don’t see it that way.

In a final question, I ask how artists like him maintain longevity in an industry designed to commodify and spit out acts at a faster rate than ever before.

“Bro, I don’t know the specific answer to that, but I know one key to that is boots to the ground authenticity. Keeping it as authentic to you whatever that means to you. I know that is one of the keys. Other than that everything else is a variable.”

“I could get hit by a bus or some shit right now… being the most you possible works. All the artists that sell the most; Kanye, Outkast, they are just themselves on a wide scale. They are vulnerable in a way that people can look at and be like:

‘Yeah. Me too’.”